Swimming in Doubt

An Ethical Assessment of Diving with Sharks

The sound of my breath through my regulator is deafening.

Kheeeeee-khooooo.

Exhaled bubbles tickle my cheek as they ascend to the surface fifty feet above.

Kheeeeee-khooooo.

My wet suit hugs me close, keeping me warm in the cool blue water.

Kheeeeee-khooooo.

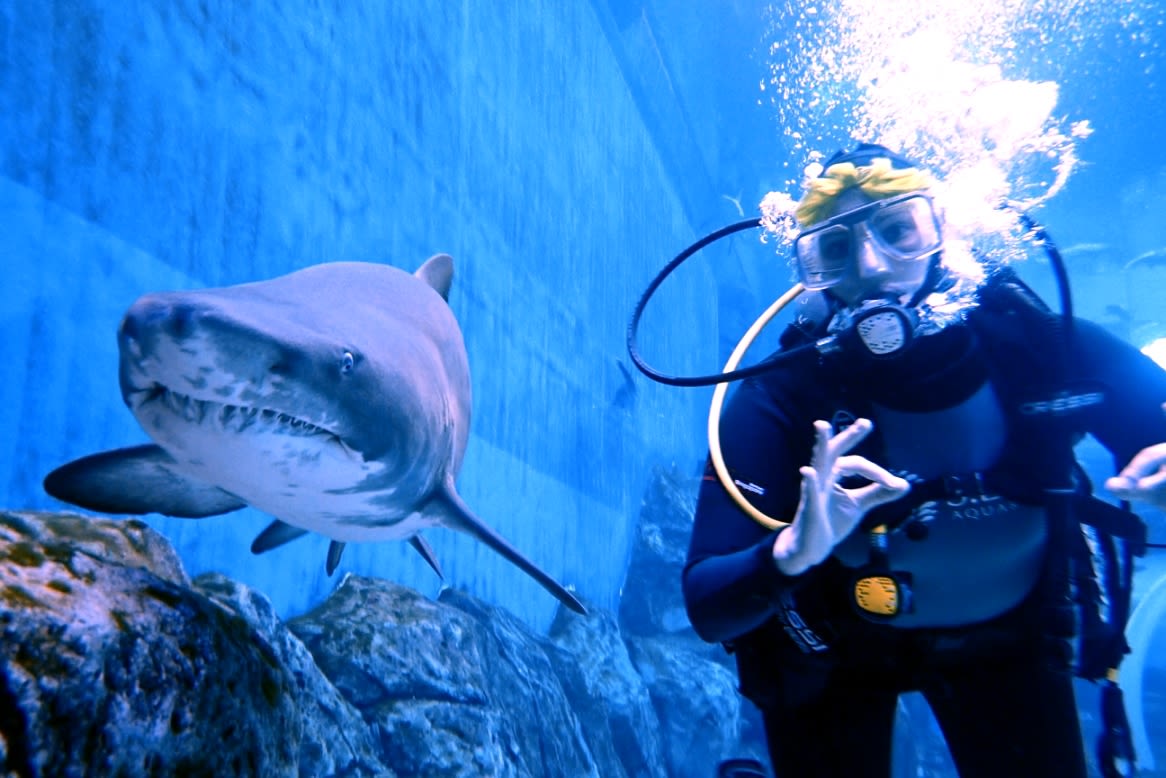

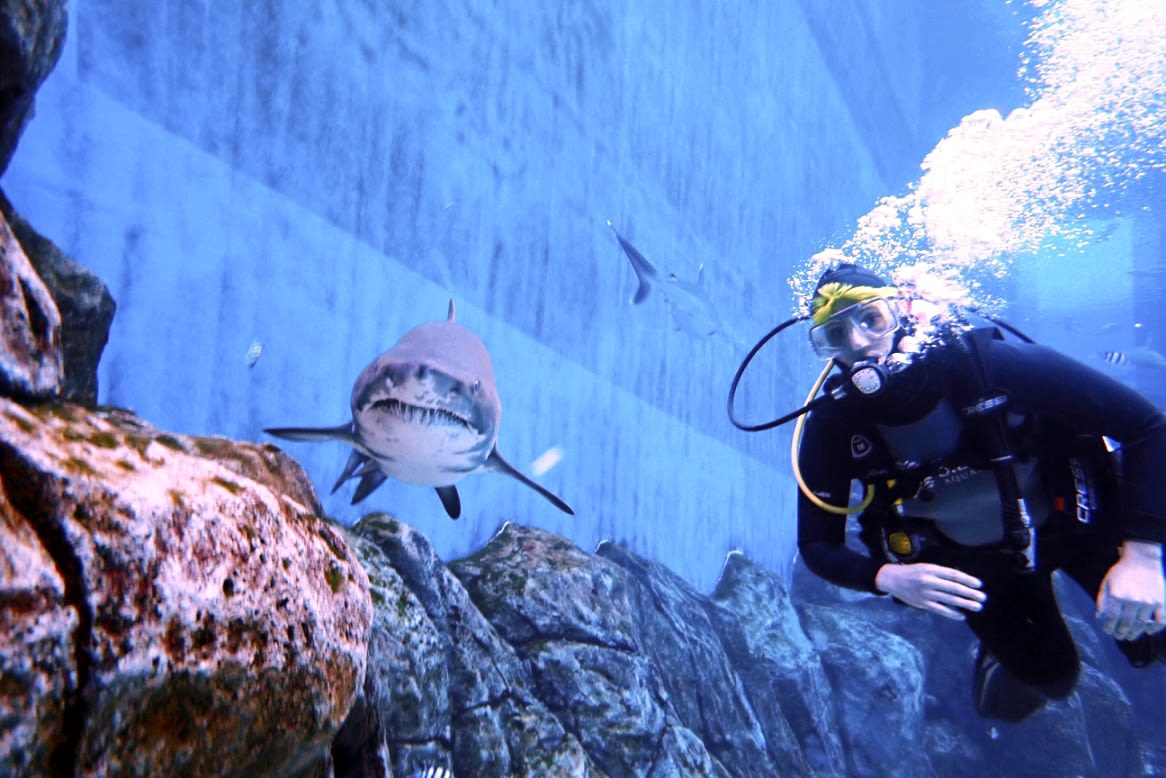

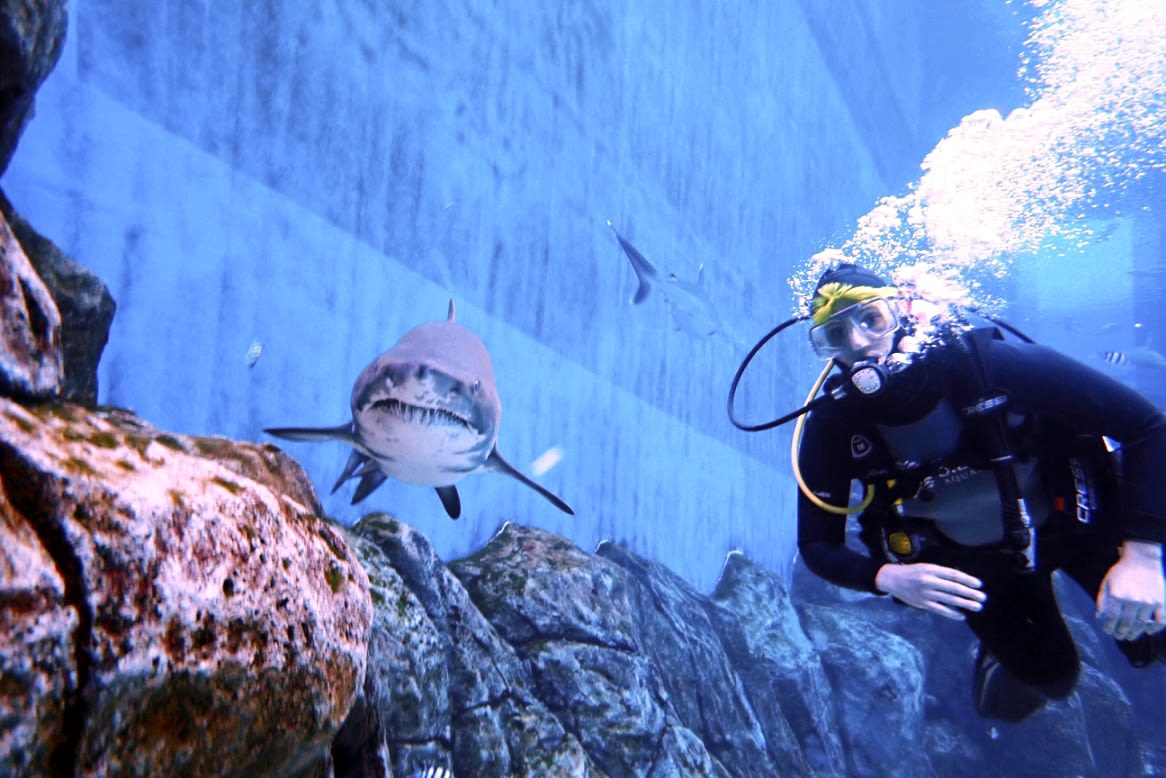

The pressure in my ears is painful from thousands of gallons of water pushing in on me from all sides. I squeeze my nose, press my tongue to my soft palate, and blow—tssseeeep! My ears equalize and I feel relief, but just for a moment. The dive instructor beckons me forward, signaling my turn for a photo opp with the star of the show. I look to my right and feel my stomach seize, my heart jump, and my adrenaline flow. Swimming alongside me, not an arm’s length away, is an eight-foot super predator with sleek grey skin and a ragged grin—a sand tiger shark.

A beat up sandbar shark swims by one of the viewing windows before my dive. Credit: Rachel Lense, 31 July 2019, Resorts World Sentosa, Singapore.

A beat up sandbar shark swims by one of the viewing windows before my dive. Credit: Rachel Lense, 31 July 2019, Resorts World Sentosa, Singapore.

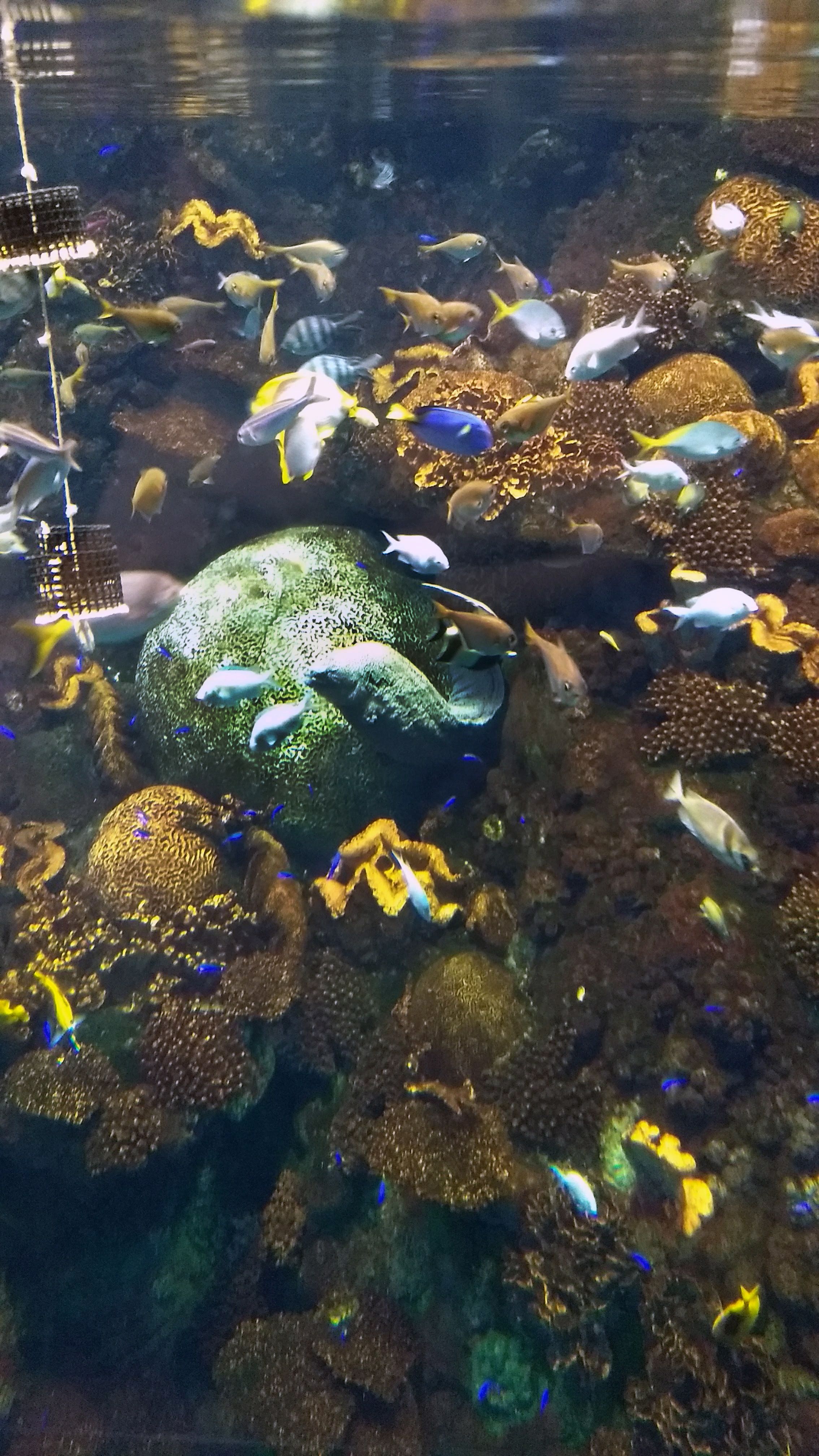

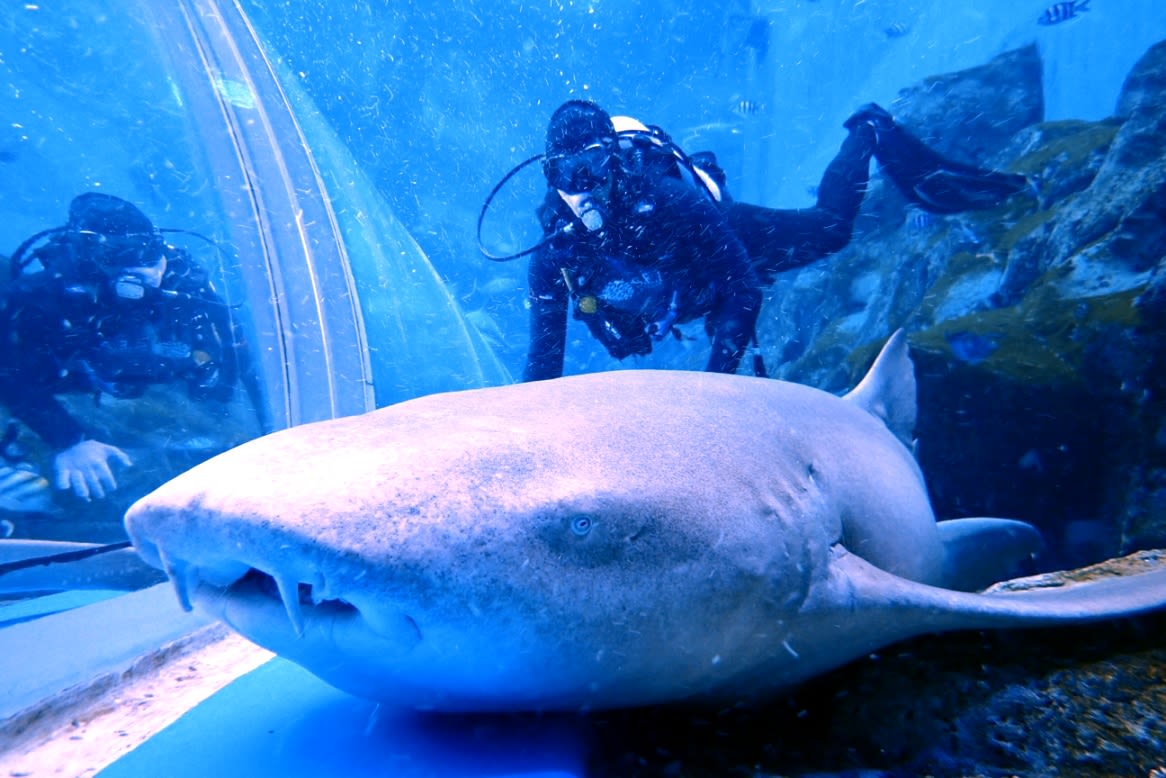

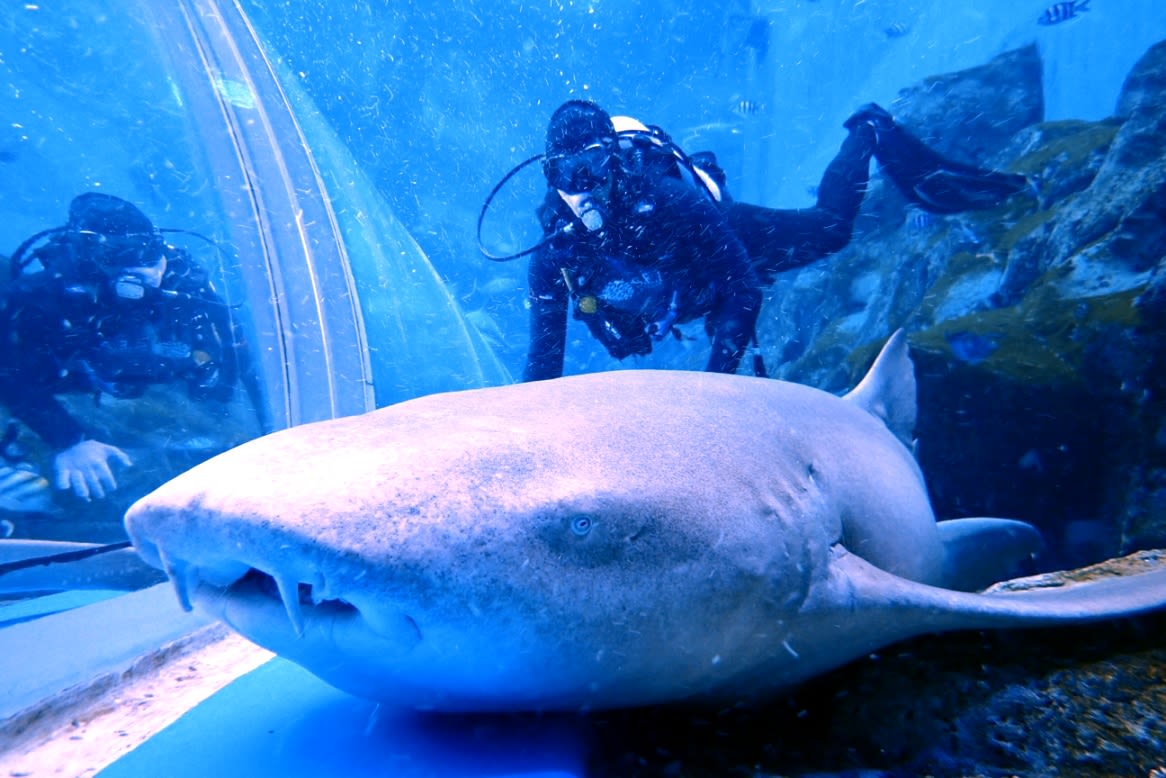

The sharks are fed before a dive to help prevent injury to the animals or divers. Credit: Rachel Lense, 31 July 2019, Resorts World Sentosa, Singapore.

The sharks are fed before a dive to help prevent injury to the animals or divers. Credit: Rachel Lense, 31 July 2019, Resorts World Sentosa, Singapore.

Now, I knew I wasn’t in any danger. An hour before, I watched from the surface as the pool of seventy-some-odd sharks from twelve different species were fed. The sand tiger shark, I also knew, was no danger to me due to its docile nature and preference for squid and crustaceans over human flesh. But something about being in its presence—seeing its majesty in person, comparing my own self barely coping in the water while it moved with gentle grace—inspired terror and wonder in me. And pity. And guilt.

Asking Questions

"Bottlenose dolphins panic and thrash in their own blood as snorkelers search for young, uninjured animals for sale to dolphinaria." Credit: Elsa Nature Conservancy/World Animal Protection

"Bottlenose dolphins panic and thrash in their own blood as snorkelers search for young, uninjured animals for sale to dolphinaria." Credit: Elsa Nature Conservancy/World Animal Protection

"Dolphin mortality shoots up six-fold during and immediately after capture. The ordeal is stressful and can cause physical injuries." Credit: COMARINO/World Animal Protection

"Dolphin mortality shoots up six-fold during and immediately after capture. The ordeal is stressful and can cause physical injuries." Credit: COMARINO/World Animal Protection

"Holding pools of newly captured animals may be quite primitive—no more than boxes lined with plastic tarps, with no filtration." Credit: WSPA/World Animal Protection

"Holding pools of newly captured animals may be quite primitive—no more than boxes lined with plastic tarps, with no filtration." Credit: WSPA/World Animal Protection

A few years before this dive, I watched the movie Blackfish on Netflix. For the unacquainted, it’s a documentary that put Sea World’s abusive treatment of orcas in the searing spotlight (and caused major financial stress on the company as a result). But it also encouraged people to consider the cruelty of exploiting animals for entertainment’s sake. Things like swim-with-the-dolphins programs in Mexico, for instance, or porpoise petting stations at zoos.

In captivity, marine mammals like whales and dolphins are highly susceptible to depression, stress, and anxiety. Among other physiological problems, they have trouble breeding and suffer high mortality rates. The monotony of shallow, bare, concrete confinement is akin to torture for such highly-social, highly-intelligent creatures. In the open ocean, they spend entire days swimming and playing at depth for miles with their pods.

But sharks are famously fish, not mammals, so I thought they were probably fine with their lot in aquariums around the world. I quashed my uneasy feelings about participating in an aquarium dive while on vacation, paid my $250, and got a front-row seat to watching dozens of apex predators swim. In circles. Forever.

When I returned home, that greasy feeling of guilt nagged me. I needed to learn more about sharks in captivity. It turns out that some larger species, such as whale sharks, do experience high mortality rates, but other signs of stress in these environments are not as well-documented or understood. This was far from the cut-and-dry answer I was hoping for.

Was my participation in an aquarium shark dive tacitly supporting animal torture?

Not necessarily.

Over the decades, and especially since the public became more concerned with animal welfare, many aquariums shifted their focus from entertainment to education and conservation. They’ve invested in their facilities to provide deeper, wider, more intellectually stimulating and authentic environments for their animals. Many have begun working with researchers and conservation teams at much higher rates. And with rapid changes in the world's oceans due to climate change, a new trend in science now views captive populations as an essential piece of the conservation puzzle. The viability of existing wild populations may very well depend on the contributions of captive ones, from studying the animals and their behaviors closely to their strategic release back into the wider world.

Then was my participation supporting the conservation of marine biodiversity?

Not necessarily.

While the general focus of many aquariums today is education and conservation, the balance between those goals and entertainment depend on the individual institution. The Monterey Bay Aquarium in Monterey, California, for instance, is one of the world’s leaders in conservation efforts. From its mission (“to inspire conservation of the oceans”) to its conservation advocacy center (Center for the Future of the Oceans), many of its decisions are made with ecological conservation in mind. But other aquariums may not have similar budgets or popular support for that kind of messaging. In 2012, the Georgia Aquarium assured their guests they would never hear the words “global warming” used during their visit.

So, if I wasn't supporting animal cruelty, but I also wasn't supporting marine life conservation, where does that leave me?

To be frank: I’m not sure.

Monterey Bay Aquarium's mini kelp forest is a microcosm of the larger forest just outside the aquarium's walls along the Pacific coast. Credit: Rachel Lense, 07 December 2019, Monterey Bay Aquarium, Monterey California, USA.

Monterey Bay Aquarium's mini kelp forest is a microcosm of the larger forest just outside the aquarium's walls along the Pacific coast. Credit: Rachel Lense, 07 December 2019, Monterey Bay Aquarium, Monterey California, USA.

A green moray eel peeks out from a crevice in a wall of artificial artificial reef in Osaka's Kaiyukan Aquarium. Credit: Rachel Lense, 16 October 2017, Kaiyukan Aquarium, Osaka, Japan.

A green moray eel peeks out from a crevice in a wall of artificial artificial reef in Osaka's Kaiyukan Aquarium. Credit: Rachel Lense, 16 October 2017, Kaiyukan Aquarium, Osaka, Japan.

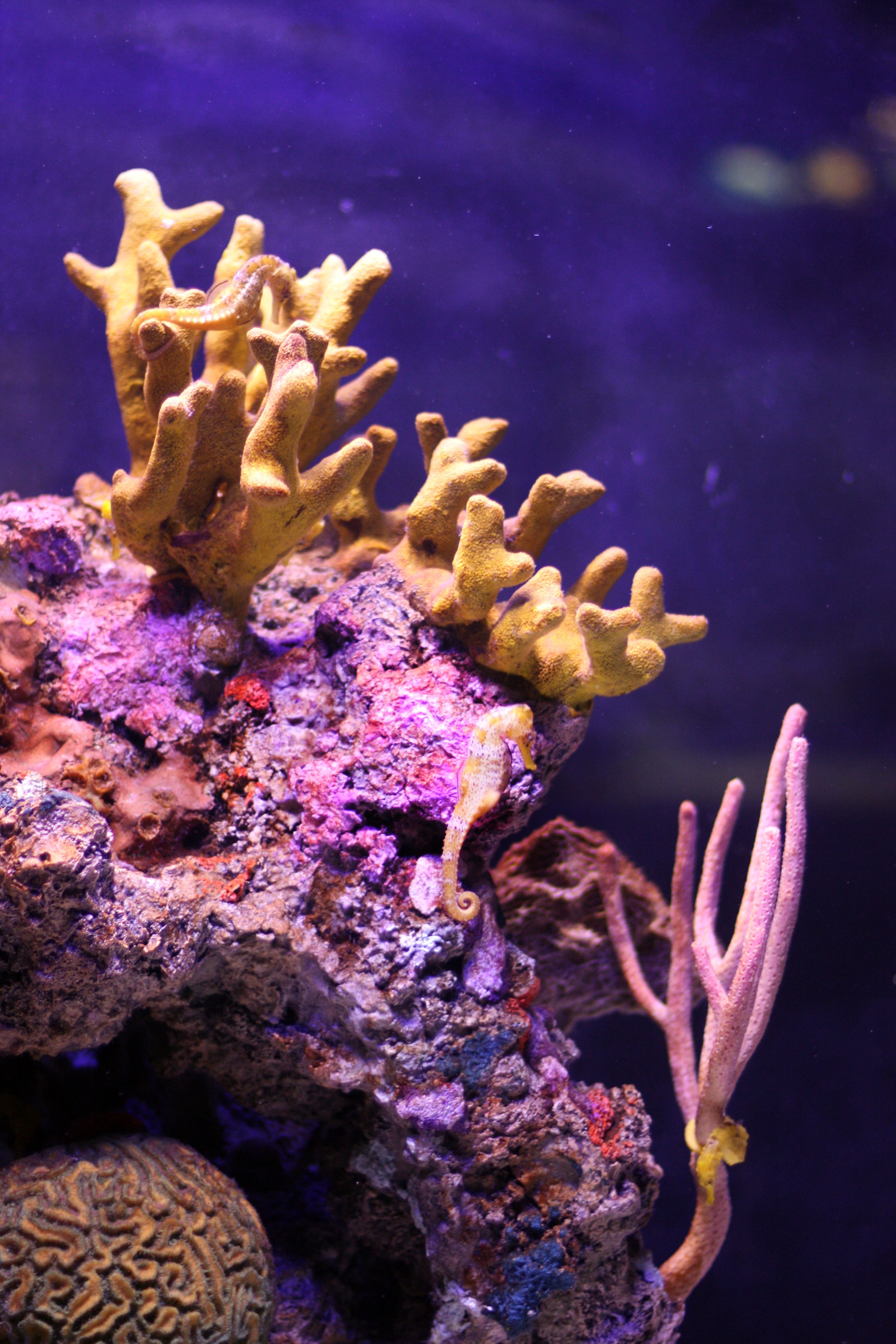

Tiny seahorses float near their colorful homes, an artificial tropical reef at Baltimore's National Aquarium. Credit: Mr.TinMD, 28 September 2008, National Aquarium, Baltimore, Maryland, USA

Tiny seahorses float near their colorful homes, an artificial tropical reef at Baltimore's National Aquarium. Credit: Mr.TinMD, 28 September 2008, National Aquarium, Baltimore, Maryland, USA

Finding Answers

I do know, however, my experience diving with sharks in an aquarium left me with a tumult of conflicting ideas and emotions. I know it left me sucked into a wetsuit, donning facemask, fins, oxygen tank, and regulator, descending through scores of sharks and tepid sea water to fifty feet below the surface. It left me equalizing pressure in my ears near the silvery skin of cuddling nurse sharks. It left me blowing bubbles and waving at children on the drier side of a sixty-foot viewing window. But ultimately, it left me with a desire to know more about the life I saw tinted blue around me, and how we all fit together in the world around us.

Will I ever dive with sharks again? I hope so, but I doubt it will be at an aquarium.

Me with a tasselled wobbegong shark, a species of carpet shark that lives in shallow coral reefs near Australia. Credit: S.E.A. Aquarium, 31 July 2019, Resorts World Sentosa, Singapore.

Me with a tasselled wobbegong shark, a species of carpet shark that lives in shallow coral reefs near Australia. Credit: S.E.A. Aquarium, 31 July 2019, Resorts World Sentosa, Singapore.

One of my dive mates waves to a visitor at the resort as she walks through a glass tunnel that bisects the giant shark tank. Credit: S.E.A. Aquarium, 31 July 2019, Resorts World Sentosa, Singapore.

One of my dive mates waves to a visitor at the resort as she walks through a glass tunnel that bisects the giant shark tank. Credit: S.E.A. Aquarium, 31 July 2019, Resorts World Sentosa, Singapore.

The sharks are fed before a dive to help prevent injury to the animals or divers. Credit: Rachel Lense, 31 July 2019, Resorts World Sentosa, Singapore.

The sharks are fed before a dive to help prevent injury to the animals or divers. Credit: Rachel Lense, 31 July 2019, Resorts World Sentosa, Singapore.

Another photo of me with the sand tiger shark. Credit: S.E.A. Aquarium, 31 July 2019, Resorts World Sentosa, Singapore.

Another photo of me with the sand tiger shark. Credit: S.E.A. Aquarium, 31 July 2019, Resorts World Sentosa, Singapore.

One of my dive mates with a tawny nurse shark by the glass tunnel. Credit: S.E.A. Aquarium, 31 July 2019, Resorts World Sentosa, Singapore.

One of my dive mates with a tawny nurse shark by the glass tunnel. Credit: S.E.A. Aquarium, 31 July 2019, Resorts World Sentosa, Singapore.