The Creek Where We Fed on Eels

The disappearance of a defining fish from the Susquehanna watershed

Swatara Creek, Pennsylvania

Cicada song spills from the trees. Their hymn eddies and flows, much like the shallow brown water that runs through Swatara creek. The drooping branches of River birch pour over the creek banks and the large leaves of American sycamores fan across the canopy high above.

A family of common mergansers cast into the water along Swatara Creek. Video source: Jules Stanley

A family of common mergansers cast into the water along Swatara Creek. Video source: Jules Stanley

Along this creek, Belted kingfishers dart over the water

and Cedar waxwings flit through the canopy.

Great blue herons and Great egrets take laborious flight from the shallows, where they fish for crayfish and channel catfish.

Even Bald eagles thrive here, raising their young and soaring overhead.

Bald eagle taking off from the bank of the Swatara. Video source: Jules Stanley

Bald eagle taking off from the bank of the Swatara. Video source: Jules Stanley

Though Swatara creek may look idyllic, it is lacking the creature that once defined its waters:

the American eel.

The American eel was once prolific in the massive Susquehanna watershed that encompasses the Swatara.

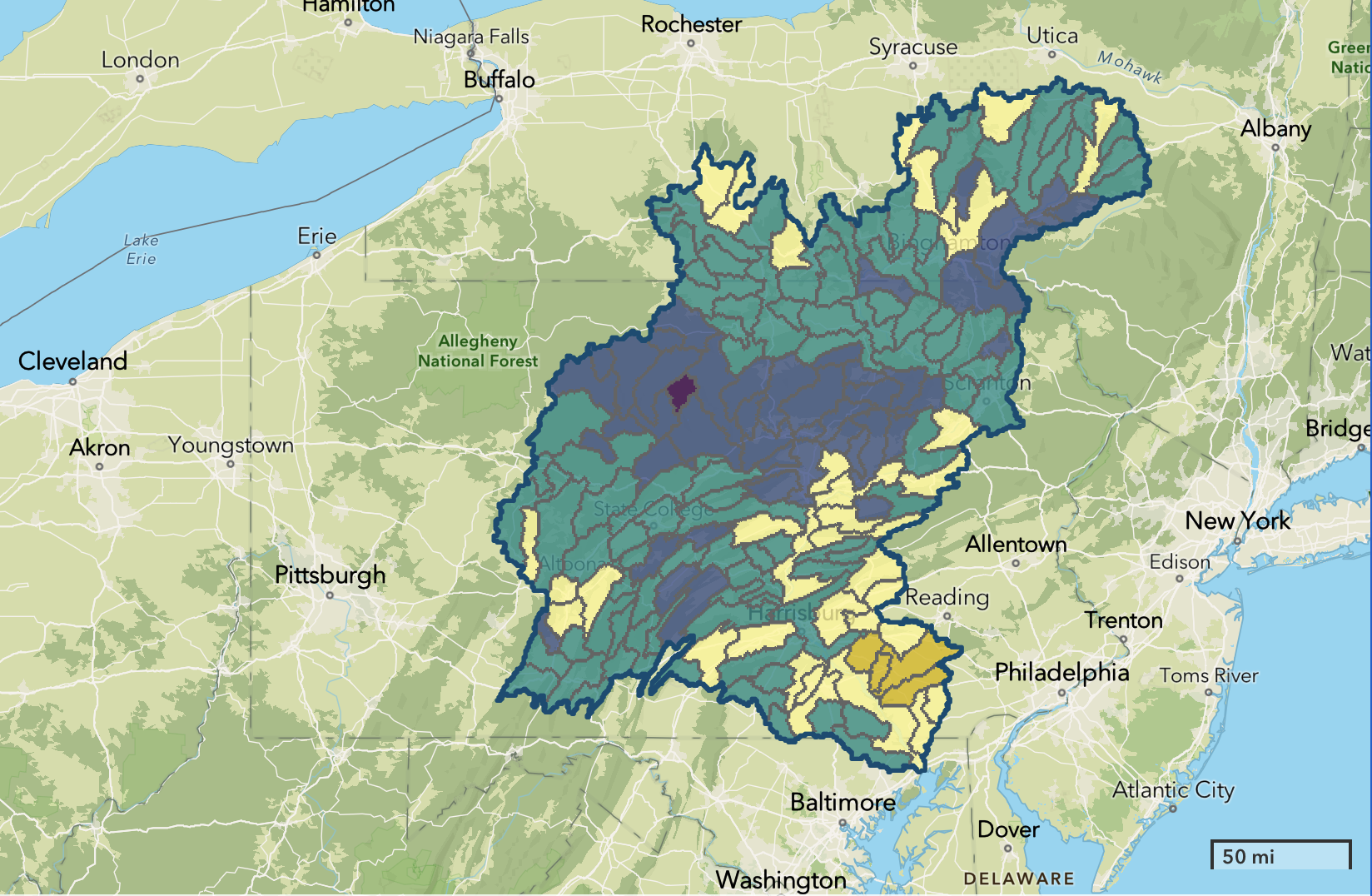

The Susquehanna watershed, which reaches across Pennsylvania and into New York and Maryland. Image source: Susquehanna River Basin Commission (SRBC)

The Susquehanna watershed, which reaches across Pennsylvania and into New York and Maryland. Image source: Susquehanna River Basin Commission (SRBC)

The name “Swatara” comes from the Susquehannock word for “where we fed on eels.” Now, dilapidated eel weirs, once used by the Susquehannock people to corral and harvest the eels, sit empty along the creek bed.

American eels are much like salmon: they split their time between fresh and saltwater. In the case of the eels, they live in freshwater rivers and streams across the Eastern United States then retreat to the Sargasso Sea to spawn. Elvers (baby eels), born in the sea, float about the saltwater as glass eels before returning to the North American continent, a migration still shrouded in mystery.

A glass eel, the transparent juvenile stage of the American eel (Anguilla rostrata) on the shore of Fire Island National Seashore. Image source: NPS

A glass eel, the transparent juvenile stage of the American eel (Anguilla rostrata) on the shore of Fire Island National Seashore. Image source: NPS

After they reach the continent, the elvers innately know to swim against the current, pushing further into the watersheds. The Susquehanna river was once a major eel throughway, leading the fish to the Swatara, among dozens of other tributaries.

An elver that is a part of the Eel in the Classroom initiative started by a member of the Susquehanna River Basin Commission. This initiative allows students to study the lifecycle of the American eel and then release the eel into its native waterways. Image source: James Shallenberger, SRBC

An elver that is a part of the Eel in the Classroom initiative started by a member of the Susquehanna River Basin Commission. This initiative allows students to study the lifecycle of the American eel and then release the eel into its native waterways. Image source: James Shallenberger, SRBC

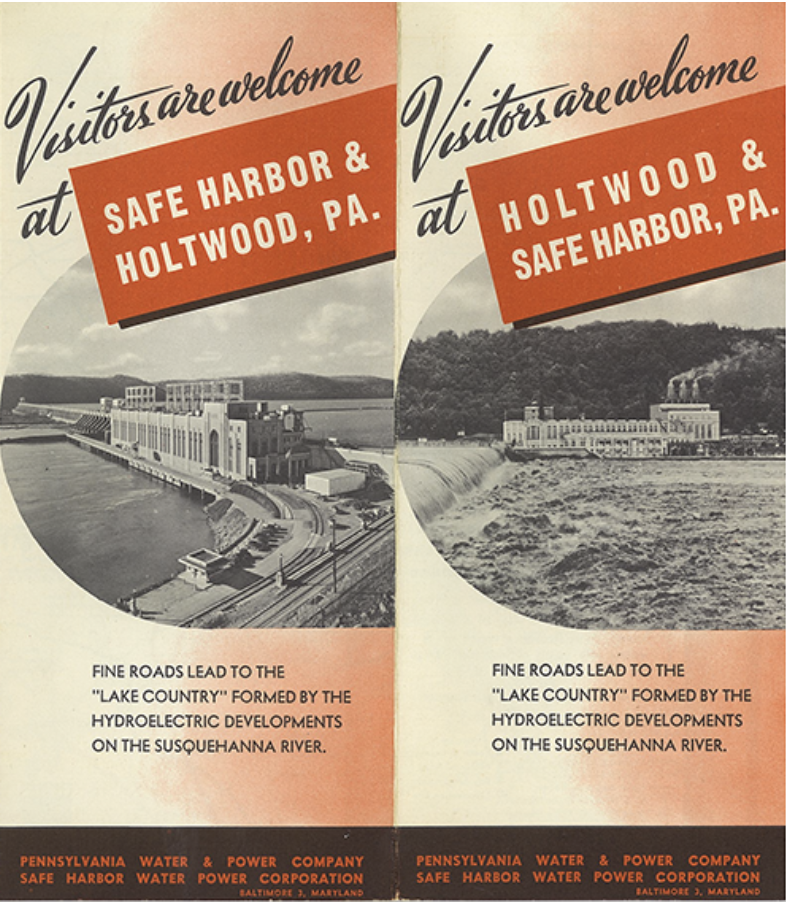

But in the 20th century, scars cut across the mile-wide river. In 1904, the York Haven Dam was built just five miles south of the Swatara confluence. The Holtwood Dam, near the southern Pennsylvanian border, was finished a few years after. Two decades later, in 1931, the Safe Harbor Dam slit through the water.

Safe Harbor/Holtwood Visitor’s Guide from 1951. Image source: unchartedlancaster.com

Safe Harbor/Holtwood Visitor’s Guide from 1951. Image source: unchartedlancaster.com

An elver about to be released upstream of the Conowingo Dam in the Susquehanna. Image source: Greg Thompson/USFWS

An elver about to be released upstream of the Conowingo Dam in the Susquehanna. Image source: Greg Thompson/USFWS

There is a labor-intensive solution to this obstacle: conservationists collect the elvers in buckets and truck them upstream of the dams.

Elvers climbing an eel ramp, at the end of which is a collection bucket (out of frame). Image source: Josh Newhard, USFWS

Elvers climbing an eel ramp, at the end of which is a collection bucket (out of frame). Image source: Josh Newhard, USFWS

An adult eel being measured by USFWS researches. Image credit: Maryland Fisheries Resource Office, USFWS

An adult eel being measured by USFWS researches. Image credit: Maryland Fisheries Resource Office, USFWS

When adult eels swim back out to sea, they confront the dams again. But this time, there is no help to get around. They have to swim under, through the hydroelectric turbines that churn the river for power. But the blades of the hydroelectric turbines act like knives, slicing through water and eel bodies alike.

When elvers return to American tributaries they face the massive dam walls, along with the extreme water pressure that powers the hydroelectric facilities.

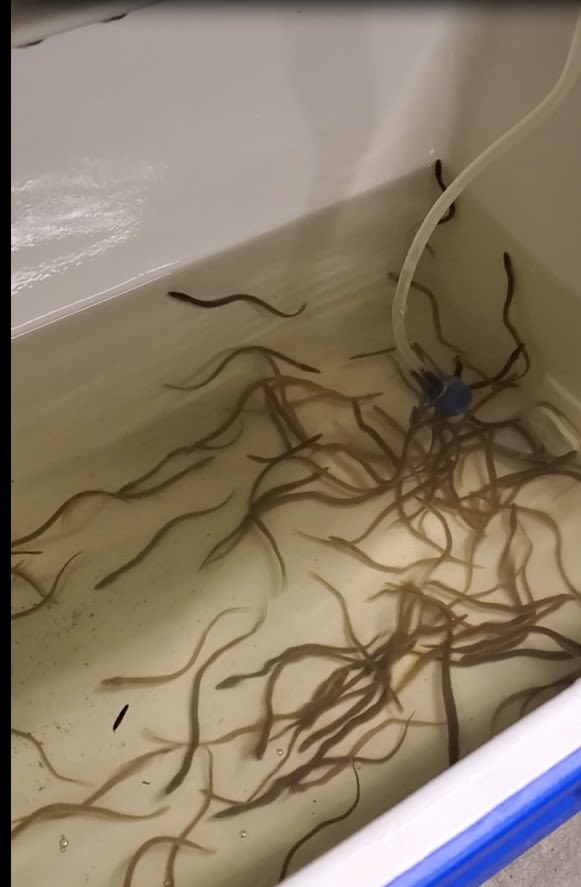

Elvers in a cooler awaiting transport upstream of the dams. Image source: James Shallenberger, SRBC

Elvers in a cooler awaiting transport upstream of the dams. Image source: James Shallenberger, SRBC

This method works well enough when the eels are small, around four to ten inches long. But adult eels can reach two to three feet in length and can weigh up to 9 pounds. Now imagine transporting buckets and buckets teeming with adult eels: most conservationists in the region can't.

Susquehanna River Basin Committee members catching injured and dead eels in the waters after York Haven Dam. Image source: James Shallenberger, SRBC

Susquehanna River Basin Committee members catching injured and dead eels in the waters after York Haven Dam. Image source: James Shallenberger, SRBC

James Shallenberger, the manager of the Susquehanna River Basin Commission’s Monitoring and Protection agency, lamented over the carnage of eels that passed through the York Haven Dam turbines:

“I’ve collected adult eels after they’ve been cut up going through the turbines. And it’s not a pretty sight. When you see an eel that’s three feet long and it’s in three different pieces… it’s pretty shocking.”

According to Mr. Shallenberger, adult eels have no truly safe solution.

But there are small steps that dams can take to help the eels.

One solution that conservations like Mr. Shallenberger are pushing asks dams to reduce or halt turbine use at night, when eels are most active, as well as during seasonal migrations.

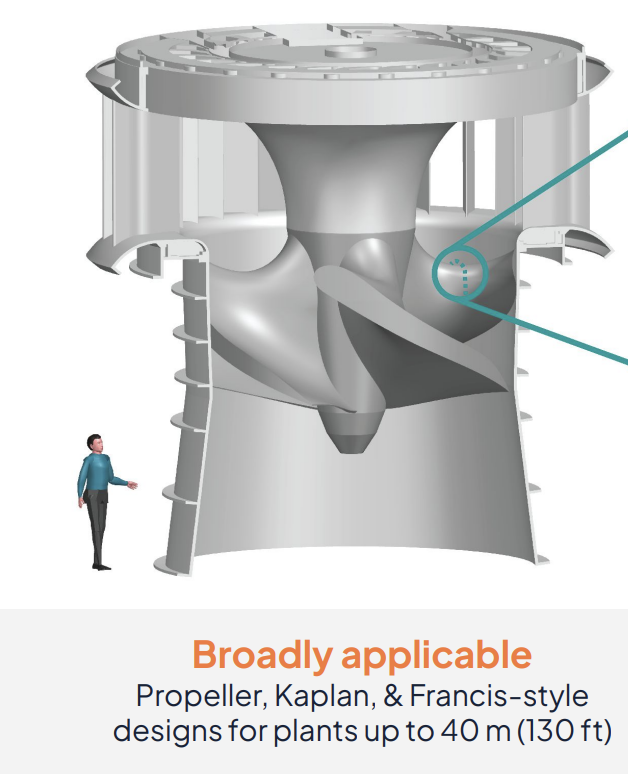

And scientists at Natel Energy of California are hopeful that the best solution is just around the bend.

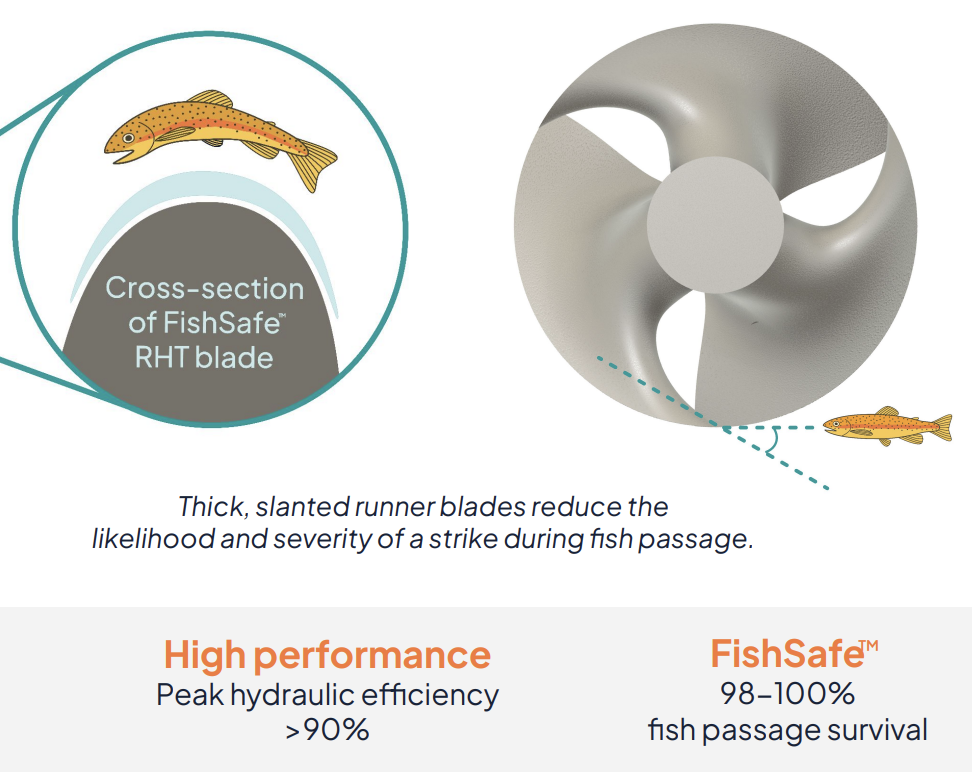

In 2022, these researchers, led by Sterling Watson, conducted a study to test the efficacy of a new hydroelectric turbine designed specifically to allow for fish migration. The turbine's curved propeller blades are designed to provide a safe area which the eels can slide over.

In the study, of the 131 adult eels that passed through the operating turbine, zero were harmed in any serious way.

Dams will continue to pose problems for eels, but innovations like Watson's FishSafe™ Restoration Hydro Turbine could provide a larger solution to their plight.

Brookfield Renewable Partners, the energy company that owns Holtwood and Safe Harbor dams, has not yet replied for comment regarding whether they will adopt fish-friendly practices like the curved turbine blades.

But, with the work of conservationists like the SRBC and USFWS, the creek where we fed on eels may one day have its eels back.

Belted kingfisher: Jack Bulmer/Unsplash. Cedar waxwing: Tyler Jamieson Moulton/Unsplash. Great blue heron: Joseph Corl/Unsplash. Great egret: Tim Wilson/Unsplash. Bald eagle: Dallas Penner/Unsplash. Eel painting: Duane Raver/USFWS. All other background images: Jules Stanley.